Hackathon Tips

I participated in the LLM Hackathon for Applications in Materials Science & Chemistry September 11-12, 2025. It was a great opportunity to think and learn about how LLMs can be used in science. It was also a chance to meet new people in the community, or collaborate live with folks I know from online. Here are some things I learned about how to get the most done in a hackathon.

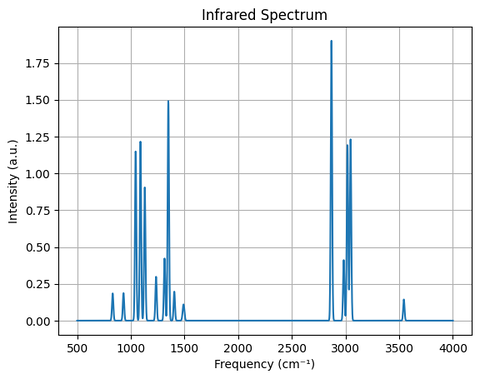

I was on the ChemGraph-IR team whose goal was to calculate the infrared absorption spectrum of a molecule given an LLM prompt requesting the IR spectrum of a named chemical.

Infrared absorption spectrum of ethanol generated by Murat Keçeli

Begin with the end in mind®

As this trademarked phrase from Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People® says, it’s a good idea to think from the beginning about what you’ll need to produce at the end of the hackathon.

Plan the deliverables

When a team starts a hackathon, it’s natural to focus first on how to start: What permissions to set up, what code to write, etc. But it’s actually a good idea to think first about what the deliverables will be. For example, for this hackathon the deliverables were a two-minute video, a submission form, and a social media post announcing the completed project.

An effective way to plan a video is with storyboards, that is the still images that provide the flow of the video. So what I would do next hackathon is start by deciding the key assets–project outputs such as graphs. That would give everyone a good starting point:

- The software developers would know what they’re working towards, for example a graph of infrared absorption intensity against frequency (cm-1).

- The video creators would know what the storyboards are so they could plan the video. It would probably have alerted the team to the amount of work that needed to go into the video. At least two of us spent most of the second day working on the video. While our ChemGraph video was perfectly fine–it was like a scientific presentation with slides and narration–other teams’ were more elaborate and were projects in themselves. Had someone focused on the presentation from the beginning, they might have come up with an outside-the-box idea.

# Source - https://stackoverflow.com/questions/18019477/how-can-i-play-a-local-video-in-my-ipython-notebook#18026076

# Posted by Viktor Kerkez, modified by community. See post 'Timeline' for change history

# Retrieved 2025-11-06, License - CC BY-SA 4.0

from IPython.display import Video

Video("/images/MethanolVibrations.mov")

Video of infrared absorption spectrum and vibrational modes of methanol made by Kevin Shen

Draft the final texts ahead of time

Our team ended up submitting the form just minutes before the deadline. Anticipating there might be a last-minute crunch, I drafted in a spreadsheet the form responses–there were “essay questions” so a significant amount of text was necessary. “Preparing for that helped a lot” according to the project leader who submitted the form. The statement of goals from the project proposal was a great starting point for drafting the submission.

Similarly, it was a good idea to draft ahead of time the LinkedIn post unveiling the ChemGraph-IR video.

Both of these were also example of another tip: If you notice something needs to be done, do it yourself if you can, and share the results with the team so they can improve it.

Prototype the output

Even before the code is ready, create a way to test the ultimate output of your project. For example, I created a simple Jupyter Notebook which prompted ChemGraph with “What is the infrared absorption spectrum of water?” This provided multiple benefits:

- I ran the prompt and found that the existing code already provided an answer based on other knowledge from the LLM itself. This alerted the team that we might need to tell the LLM not to use its background knowledge, and instead use the new code in progress.

- The existing code output the steps used, letting the team know what preparatory steps were taken, which could inform where the new code should pick up.

- After my pull request was merged, it gave team members a way to check the end-to-end output of the in-progress code.

- It provided a starting point for prompt engineering: A team member later suggested we add “using ASE and TBLite” (the particular tools used to calculate the spectrum) to the end of the prompt.

Commit code early and often

Even if you don’t think your branch isn’t all done, or may not be that useful, submit a pull request when it’s largely complete. I did that and marked it as draft, but the project maintainer wisely merged it. That let others build on it.

And from the consumption side, when I was working on the presentation, it was helpful to have the latest code merged so I could pull it and run the product to produce the output.

Realize that LLM performance can lead to errors

Particular to this type of hackathon, it became apparent that the performance of the LLM can cause “errors.” For example, if the recursion limit was too low, ChemGraph couldn’t generate a molecular structure. Increasing the recursion limit (which increases the cost!) solved the problem. Or you might find that using a less-advanced LLM fails, while another more-advanced LLM works.

Set up credentials early

When you have limited time, it’s important to get participants able to contribute as soon as possible. Setting up credentials such as a API token for an LLM lets people get going on their own.

Keep track of people and their roles

Our team had members sign up for their primary and secondary roles on a shared spreadsheet. That was a great idea because we knew who to talk to about a given aspect of the project.

In fact, it would have been useful to analyze that sheet and notice that no one had signed up to work on the presentation. In the end it worked out because a couple of us took on the presentation at the start of the second day, but ideally someone should have thought about the presentation from the beginning.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone on the ChemGraph-IR team, particularly the organizers Murat Keçeli and Thang Pham! And to Ben Blaiszik for organizing the hackathon, and David Elbert and Mohd Zaki for hosting me at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Check out this article in Science about the hackathon.